Crevasse–Squeeze Ridges at Breiðamerkurjökull, Iceland

Glaciers are incredible sculptors of the Earth. As they flow across the Earth’s surface, they create unique landscapes by carving and redistributing sediments beneath and at the edges of the ice. Glacially formed landscapes can vary considerably, often containing a variety of different landforms, depending on factors such as, how fast the ice flows, how the ice interacts with the ground beneath it, and how much meltwater and sediment is available for erosion and transportation. This means that landscapes, and specific landforms, can provide us with valuable information regarding glacial processes. When glaciers melt and retreat, the shaped landscapes are exposed, allowing us to observe landforms and better understand how the ice has behaved.

Ice is deformable, or ‘plastic’, meaning that it can stretch with movement, similar to stretching an elastic band. However, if the ice flows too quickly, it can impose stresses on the ice resulting in fracturing and crevassing. Crevasses are noticeable at the ice surface, but they can also form from the base of the ice upwards or extend the entire depth of the ice.

There is a lot of uncertainty about the processes that occur beneath the ice as we cannot directly observe them. However, due to the weight and flow of ice, combined with the production of meltwater, we can make reasonable assumptions about pressure and hydrological regimes. It is suggested that variations in pressure and hydrology at the bed of ice can cause sediments to be squeezed up into basal or full-depth crevasses. When the surrounding ice eventually melts, these sediments are preserved on the landscape as elongated, narrow, sharp-crested ridges, that we recognise as ‘crevasse-squeeze ridges’.

There are many crevasse-squeeze ridges in the proglacial area of Breiðamerkurjökull and our aim for this project was to look inside these ridges and better understand how they were formed. We did this using two methods:

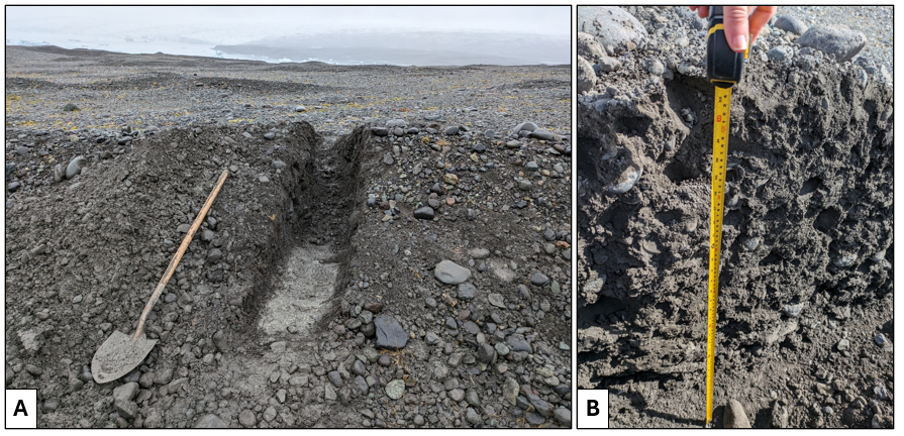

- This method involves excavating a trench across the landform and observing the sediment structures inside the ridge, as well as taking measurements of the shape and orientation of rocks within the sediments. The excavated trench was filled back in once observations had been made, ensuring that the landscape was left originally found.

- This is a non-intrusive method that works by pulling a device over the target landform whilst it emits pulses of electromagnetic waves into the ground. These waves are then reflected back up to the receiver providing an image of the subsurface.

Aerial drone imagery was also captured to enable us to view the wider spatial distribution of CSRs across the study area.

These methods combined will provide us with very detailed information about the internal architecture of crevasse-squeeze ridges in the area and help us to better understand the glacial processes that occurred to create them.

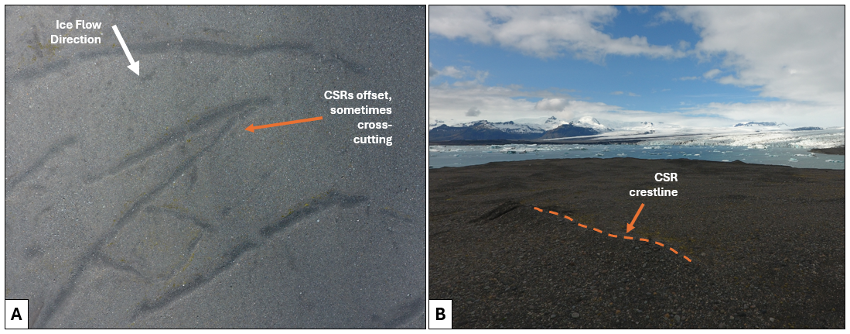

FIGURE 1. A) Aerial drone image showing the spatial distribution of crevasse-squeeze ridges (CSRs) located in the proglacial area of Breiðamerkurjökull, Iceland. B) Oblique image of chosen CSR for observations.

FIGURE 2. A) Excavated trench of target CSR in the proglacial area of Breiðamerkurjökull, Iceland; B) Image of the inside of target CSR from which sedimentological observations were made.

FIGURE 3. Glacier Adventure drop–off site; a further 3 km hike with equipment to the study area (Gwyneth E. Rivers, Sheffield Hallam University).

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend thanks to Haukur Ingi Einarsson and the guides at Glacier Adventure, who helped us to and from the site with our equipment every day and provided us with excellent knowledge of the local area. Thanks also to Sigurður Óskar Jónsson,Vatnajökull National Park manager, for granting our research permit – and warning of potentially hostile birds! It is a privilege to learn and share insights via collaborations such as this.

This project was funded by Sheffield Hallam University, and conducted by Gwyneth E. Rivers*, Sheffield Hallam University, Dr Andy Emery, Wessex Archaeology, and Dr Robert D. Storrar, Sheffield Hallam University.

*Gwyneth E. Rivers; email: [email protected]; web: https://gwynethrivers.wixsite.com/gwyn-rivers